For the first time, researchers described the structure of a special type of amyloid beta plaque protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression, and showed that lecanemab, a new treatment, can neutralize it.

Reporting May 10 in the journal Neuron, scientists showed the small aggregates of the amyloid beta-protein could float through the brain tissue fluid, reaching many brain regions and disrupting local neuron functioning.

The research also provided evidence that lecanemab, the newly approved AD treatment, could neutralize these small, diffusible aggregates.

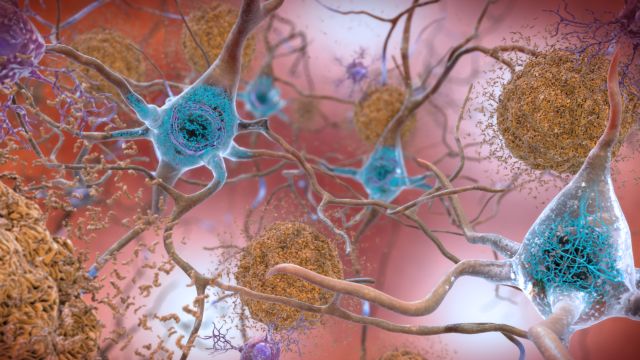

As a cause of dementia, AD affects more than 50 million people worldwide. Previous research has discovered that AD patients have abnormal build-up of a naturally occurring substance—amyloid-

beta protein—in the brain can disrupt neurotransmission. Currently, there is no cure for the disease. But in recent years, scientists have developed new treatments that can reduce AD symptoms such as memory loss.

“The paper is timely because, for the first time in human history, we have an agent that can actually treat people with Alzheimer’s in a way that could slow their cognitive decline,” says Dennis Selkoe, the paper’s corresponding author at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “And we’ve never been able to say those words until the last few months.”

In January, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved lecanemab, an antibody therapy for treating AD. In a Phase III clinical trial, lecanemab slowed cognitive decline in patients with early AD.

Scientists suspect the drug’s positive effect may be associated with its ability to bind and neutralize soluble amyloid beta protein aggregates, also known as protofibrils or oligomers, which are tiny, freely floating clumps of the amyloid beta protein. These small clumps can form in the brain before aggregating further into large amyloid plaques. The small aggregates can also break off and diffuse away from amyloid plaques that are already there.

“But nobody’s really been able to define with any structural rigor what is a ‘protofibril’ or ‘oligomer’ that lecanemab binds to,” says first author Andrew Stern, a neurologist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Our work identifies that structure after isolating it from the human brain. That’s important because patients and drug developers will want to know what exactly lecanemab binds to. Could that reveal something special about how it works?”

Stern, Selkoe and their team successfully isolated the free-floating amyloid beta aggregates by soaking postmortem brain tissues from typical AD patients in saline solutions, which were then spun at high speed. These tiny aggregates of amyloid beta protein were prone to travel through tissues and access important brain structures such as the hippocampus, which plays a major role in memory.

The team demonstrated that the extracted amyloid beta aggregates could impair brain cell function, but the drug lecanemab could reverse the damage in a petri dish. Working with colleagues at the Laboratory for Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, they determined the atomic structure of these tiny aggregates, down to the individual atom.

“If you don’t know your enemies, it’s hard to defeat them,” Selkoe says. “It was a very nice coincidence that all this work we were doing came right alongside the time that lecanemab became widely known and available. This research brings together the identity of the bad guy and something that can neutralize the bad guy.”

Next, the team plans to observe how these tiny amyloid beta aggregates travel through living animal brains and study how the immune system responds to these toxic substances. Recent research has shown that the brain’s immune system reaction to amyloid beta is a key component of AD.

“If we can figure out exactly how these tiny, diffusible fibrils exert toxicity, then maybe the next AD drugs can be better,” Stern says.

MORE INFO:

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Davis Alzheimer’s Prevention Program at BWH, and the UK Medical Research Council.

REFERENCE:

Stern et al. “Abundant Aβ fibrils in ultracentrifugal supernatants of aqueous extracts from Alzheimer’s disease brains” Neuron, May 10, 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.007