As a dementia silently erodes nerve cell networks in the brain, it disrupts self-referential thinking. That means a person is unable to see changes in themselves, known as anosognosia. Understanding how this condition affects getting an evaluation and making decisions allows all of us to plan for a better outcome.

The Word That Changes Everything: Anosognosia

Let’s break down this important term:

• A is a Greek prefix meaning “without” or “lack of”

• Nosos means “disease”

• Gnosia means “knowledge” or “perception”

Anosognosia literally means “lack of knowledge of the disease.” As dementia damages brain connections, it frequently disrupts the ability to make comparisons in time and space. This means a person becomes unable to see or appreciate changes in themselves. It’s not a choice; it’s a symptom of the disease itself.

Research shows that anosognosia is present in over 28% of individuals with mild Alzheimer’s disease, increasing to over 91% in more severe stages. Think about that: by the time dementia becomes severe, nearly everyone affected has lost the ability to recognize their own impairment or see how they have changed.

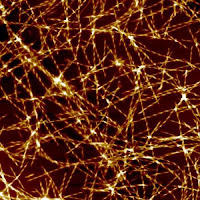

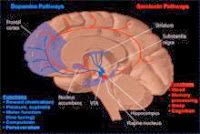

To understand anosognosia, we need to understand how aging affects the brain. Our 80 billion neurons communicate through trillions of specialized connections called synapses, forming networks which allow the high-level thinking we take for granted every day.

With aging, these networks begin to decay. We can easily see changes in our skin with spots on or face, arms or legs, and are unable to see similar types of changes in our brains. This includes a breakdown in the insulation system surrounding our nerve cells called myelin. That leads to delayed or lost messages with more “tip of the tongue” moments. Changes in the myelin within our brains can be seen on MRI scans starting in our 40s. These indicate damage within the communication highways connecting different brain regions into working networks. When the networks responsible for self-awareness are damaged, anosognosia emerges. The person living with dementia fills in memory gaps with their own explanations, creating a separate reality that seems just as valid as ours.

Should I Be Concerned?

While we can all occasionally forget a lunch meeting or the name of an acquaintance, certain changes should trigger concern.

Key warning signs include:

- Memory loss disrupting daily life: Forgetting important dates and relying more on family members to keep track of those details.

- Problems with language: Stopping mid-sentence or substituting descriptions for a word.

- Difficulty with familiar tasks: unable to organize a grocery list or manage finances as you did in the last years.

- Confusion with time or place: Forgetting where you are or how you got there.

- Poor judgment: Making unusual mistakes around money or neglecting personal hygiene.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities: Consistently absent from gatherings and losing interest in hobbies.

- Changes in mood and personality: Suspicion that others are taking things (lost items).

- Trouble understanding spatial relationships: this could be seen with driving issues and falls.

If these challenges interfere with daily life, a medical evaluation becomes essential.

Working Around the Communication Barriers

A general fear of dementia contributes to an avoidance of discussing this condition and planning a future which might contain it. And as many of us know, the people who most need an evaluation are often the least able to recognize that need because of anosognosia.

I recall quite clearly the unease in my heart when my mom began to miss our weekly phone calls. Then came the day at the county fair when she took our four-year-old daughter to a food booth and came back alone. Total panic descended with the unwanted reality that she was impaired, and our future together was permanently changed. But perhaps the most frustrating part of that journey wasn’t the memory loss itself—it was my mother’s absolute certainty that nothing was wrong.

How do we get loved ones to see a doctor when anosognosia disrupts self-awareness? We could try normalizing cognitive screening at 65-70 years of age to get a solid point for comparison at a later time. You can also approach it as something you’re interested in for yourself and invite your partner to join you; moving focus away from the person who needs help but is unable to see it. This type of strategy can be useful in many situations.

Convincing a parent they need to move out of their old apartment could be prompted by a local mandated upgrade in windows to save energy. The “temporary” stay in assisted living while this construction goes on might drag on for months or even years due to delays beyond your control. Be creative while grounded in plausible reality here can open many doors.

Two valuable screening tools that family members can complete are the Eight-Item Informant Interview (AD8) and the Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS). Both of these can be found online and bringing a completed form to a medical appointment demonstrates evidence of change and need for further evaluation.

What You Can Do Today: Reducing Your Risk

While we await more treatments, substantial research demonstrates that lifestyle interventions reduce dementia risk. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER study) showed that a multifaceted plan including diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring improved or maintained cognitive functioning in at-risk individuals. So don’t forget to ask your doctor to check for treatable conditions including strokes, medication side effects, vitamin deficiency, thyroid disease, and sleep disorders.

Lifestyle areas to concentrate on include:

Diet: Studies show reduced dementia risk with a Mediterranean-type diet emphasizing fresh vegetables, fruits, nuts, beans, and whole grains with small amounts of fish, eggs, dairy, and meats – all minimally processed.

Exercise: If exercise was available as a daily pill, it would be the most prescribed medication in this country. Physical activity releases beneficial proteins, triggers endorphin release, reduces inflammation, and facilitates growth of new cells in the hippocampus (our memory center). Aim for 150 minutes of a moderate activity spread throughout the week.

Getting a good night’s sleep: During deep sleep we consolidate memories and drain waste products from our brain. Prioritize a healthy sleep routine and regular schedule.

Social stimulation and keeping the brain engaged: Learning new things and staying connected helps keep our brains healthy.

We Can Choose How to Approach an Existential Crisis

Silently losing our memory and ability to care for ourselves with a dementia is probably the best definition of an existential crisis many of us might come up with. Choosing what level of care and support we want if this situation arises prevents the emotional strain and financial burden so many families are familiar with.

The Medical Model prevalent in the United States focuses on treating medical conditions, maximizing safety, and preventing illness. This has clear benefits, but following this path in a dementia often leads to a gradual loss of autonomy and dignity. As brain damage spreads, adding even more assistance seems a necessary response, until a loved one has lost all independence. Focusing on keeping them “healthy” can support existence in this condition, lingering for years.

The Social Model more common in European countries offers an alternative. This is exemplified in the Dementia Care community Hogeweyk, outside Amsterdam. Here the focus is on quality of life, autonomy, and allowing for a natural life-course ending. Residents with moderate to severe dementia wander freely, with access to shops, restaurants, and social activities. There are more risks in this environment and with mishaps caregivers may default to observation and comfort care more easily than the aggressive medical interventions integrated into our medical model. When I discuss this with people, most say they would prefer that option if given a choice. So let’s make our choices clear while our thinking is still crystal clear.

Starting these Difficult Conversations and Sharing Choices

My family has said to me: “Mom, not everyone is comfortable talking about death over the dinner table”. OK, so then how do we bring up these important topics? Given what we understand about progressive loss of self-awareness in anosognosia, we should all document clearly what conditions we do NOT want to be living in and what is important to us thinking about our end of life. Here are some practical steps:

1. Try using conversation starters to help launch valuable conversations about end-of-life priorities such as:

- Go Wish card game (https://codaalliance.org/go-wish/)

- Five Wishes (https://www.fivewishes.org/for-myself/)

2. Complete a healthcare directive addendum. General Advance Directives don’t address the many grey areas inherent to dementia. You need specific language about dementia care, such as:

- If I can no longer make my own decisions due to a dementia, I do not want to prolong my life, even if I seem relatively happy.

- Do not agree to any diagnostic tests or treatments that might be burdensome or painful to me and keep me in a compromised state.

- Please keep me out of potential physical pain with opiates and other strong medications if I become injured or ill.

- Never assist, coax or force me to eat. Let me eat whatever I want and am able to feed myself.

3. Use the Dementia Values and Priorities Tool. This document helps you specify exactly what type of care you want in specific situations: https://compassionandchoices.org/dementia-values-tool/

4. Designate the right decision-maker. Choose someone who can make tough decisions quickly and will honor your wishes even if other family members disagree.

5. Share your choices widely. Send your documented preferences to family members, your attorney, and medical providers.

The Promise of New Treatments

We are finally beginning to turn dementia into another chronic illness, such as heart disease. The FDA approved two new medications in 2023 and 2024; lecanemab and donanemab. These both remove abnormal amyloid fibrils or plaques which collect early in the brains of persons with Alzheimer’s Disease. Removing abnormal amyloid with these antibody treatments can slow the course of decline in early Alzheimer’s. There are some associated risks, and as with everything in medical care we need to balance potential benefits with those risks. Evidence suggests that if these anti-amyloid treatments are started early, symptoms can stay mild for much longer. So adjust your attitude with a new mantra: Time lost is brain lost!

And even more tools are being studied for release. Currently, over 100 potential medications are in development targeting different pathways which all contribute to the loss of cells in a dementia. Scientists are exploring ways to prevent the accumulation of toxic proteins, suppress inflammation, support nerve cell growth, remodel synaptic connections between nerve cells and much more.

As discussed, these treatments work best in the earliest stages which is often before people recognize significant problems. This brings us back to anosognosia; the condition that can block early detection and treatment. With better understanding of this barrier, we are in a better position to approach evaluation, treatment, and care planning.

Looking Forward with Hope and Realism

Over 7 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease in 2025 and there are nearly 12 million people providing unpaid care for relatives or friends living with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. About 80 percent of that care takes place at home, and the burden is expected to increase as our population ages.

Understanding anosognosia changes how we approach every aspect of the dementia journey. It explains why our loved ones resist evaluation, why they don’t see the need for help and why they can’t understand our concerns. This underscores why we must all plan ahead, before this condition makes planning impossible.

Prevention strategies make a difference and give us actionable steps. And following the information offered in this journal offers countless opportunities. The new treatments offer genuine hope and will help bring important conversations to the dinner table and our daily discussions.

By breaking down fear and stigma, understanding how to work around anosognosia, normalizing cognitive screening and documenting preferences we can navigate memory loss and change the course. We can also better honor autonomy, even as independence fades.