Plaque is the prime suspect behind Alzheimer’s. Amyloid-beta combines to form oligomers, which make up the plaque that clogs up the Alzheimer’s brain. Though we know all this, we are still in the dark about how to stop the process. See how supercomputers are shedding new light.

Researchers studying peptides using the Gordon supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC) at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) have found important ways to elucidate the creation of the toxic oligomers that make up the plaque associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Igor Tsigelny, a research scientist with SDSC, the UCSD Moores Cancer Center, and the Department of Neurosciences, focused on the small peptide called amyloid-beta, which pairs up with itself to form the dimers and oligomers.

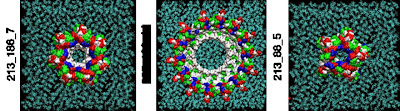

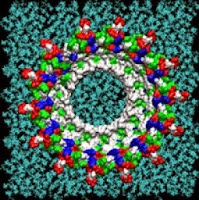

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Single amyloid-beta monomers can pair up to form a variety of dimers that can aggregate into larger peptide rings that reside on cell membranes such as those pictured. This process has been implicated in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. This visualization shows the possible rings which have the most favorable energies of interactions with the membrane. The residues are colored white to represent apolar or hydrophobic areas, green for the polar or hydrophilic areas, blue to show a positive charge, and red to show a negative charge.

Credit: Image by Igor Tsigelny, SDSC and UC San Diego; Eliezer Masliah, UC San Diego

The scientists surveyed all the possible ways to look at the dynamics of conformational changes of these peptides and the possibility that they might organize into the oligomers theorized to be responsible for the degenerative brain disease. In the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, the researchers suggest their results may generate new targets for drug development.

“Our research has identified amino acids for point mutations that either enhanced or suppressed the formation and toxicity of oligomer rings,” said Tsigelny, the study’s lead author. “Aggregation of misfolded neuronal proteins and peptides may play a primary role in neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease.”

Tsigelny also noted that recent improvements in computational processing speed have allowed him and other researchers to use a variety of tools, including computer simulations, to take new approaches to examining amyloid-beta, which has proven too unstable for traditional approaches such as x-ray crystallography.

The researchers investigated the single and dimer forms of the peptide with a combination of computational methods including molecular dynamics, molecular docking, molecular interactions with the membrane, as well as mutagenesis, biochemical, and electron microscopy studies. They then looked at how those dimers interacted with additional peptides and which larger structures resulted. The researchers found that depending on their configurations, some dimers did not lead to any further oligomerization and some form toxic oligomers implicated in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Remarkably, we showed a greater diversity in amyloid-beta dimers than previously described,” said Eliezer Masliah, professor of pathology and medicine at UC San Diego, and a member of the research team. “Understanding the structure of amyloid-beta dimers might be important for the design of small molecules that block formation of toxic oligomers.”

Based on their results, the researchers were able to identify key amino acids that altered the formation and toxicity of oligomer rings. “Our data is only theoretical, but there is a good chance the oligomers we have been modeling exist for real,” noted Masliah. “Some important recent publications have come out that support our work.”

The in silico experiments allowed the single amyloid-beta monomers to associate randomly, according to Masliah. However, he noted that within the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, the formation of oligomers and fibrils depends on any number of biochemical influences such as peptide concentration, oxidation, neurotoxins, and acidity.

According to the researchers, their work implicates a more dynamic role for the amyloid-beta dimers than previously thought. It also suggests that the way dimers form and then grow into larger structures is a rapidly changing process.

“This, as well as previous results, suggests that targeting selected amyloid-beta dimers may be important in an effort to ameliorate the episodic memory described in mild cognitive impairment and the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Masliah.

Masliah and Tsigelny’s collaborators included UC San Diego’s Yuriy Sharikov, Valentina Kouznetsova, Jerry Greenberg, Wolfgang Wrasidlo, Tania Gonzalez, Paula Desplats, Sarah E. Michael, Margarita Trejo-Morales, and Cassia Overk.

Source:

University of California, San Diego

Journal Reference:

- Igor F. Tsigelny, Yuriy Sharikov, Valentina L. Kouznetsova, Jerry P. Greenberg, Wolfgang Wrasidlo, Tania Gonzalez, Paula Desplats, Sarah E. Michael, Margarita Trejo-Morales, Cassia R. Overk, Eliezer Masliah. Structural Diversity of Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-β Dimers and Their Role in Oligomerization and Fibril Formation. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2014 DOI: 10.3233/JAD-131589

We can find the reference of the scientific articles and part of the abstracts that proof that betamyloid accumulation it is NOT the cause and do NOT triggers late o set AD , searching in this site for the post (in the Comments) of february 19, 2014 , in the COMMENTS of the post with the title:

"Alzheimer's Proscratination Therapy" (in the comments).

http://www.alzheimersweekly.com/search?updated-max=2014-02-19T04:34:00-05:00&max-results=9