Neuroscientists from Australia’s University of Queensland found ultrasound technology can boost cognitive function without clearing amyloid plaques.

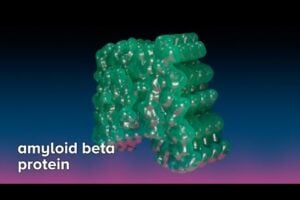

Amyloid plaque is the culprit behind Alzheimer’s. For more than a decade, researchers focused on using ultrasound to open the BBB (Blood-Brain Barrier) so that microbubbles could get through to help clear amyloid plaque.

After a decade of research applying ultrasound to transgenic mouse models, neuroscientists from The University of Queensland (UQ) in Brisbane, Australia, have found that ultrasound technology can boost cognitive function without clearing amyloid plaques. These protein aggregates in the brain are characteristic markers of the condition.

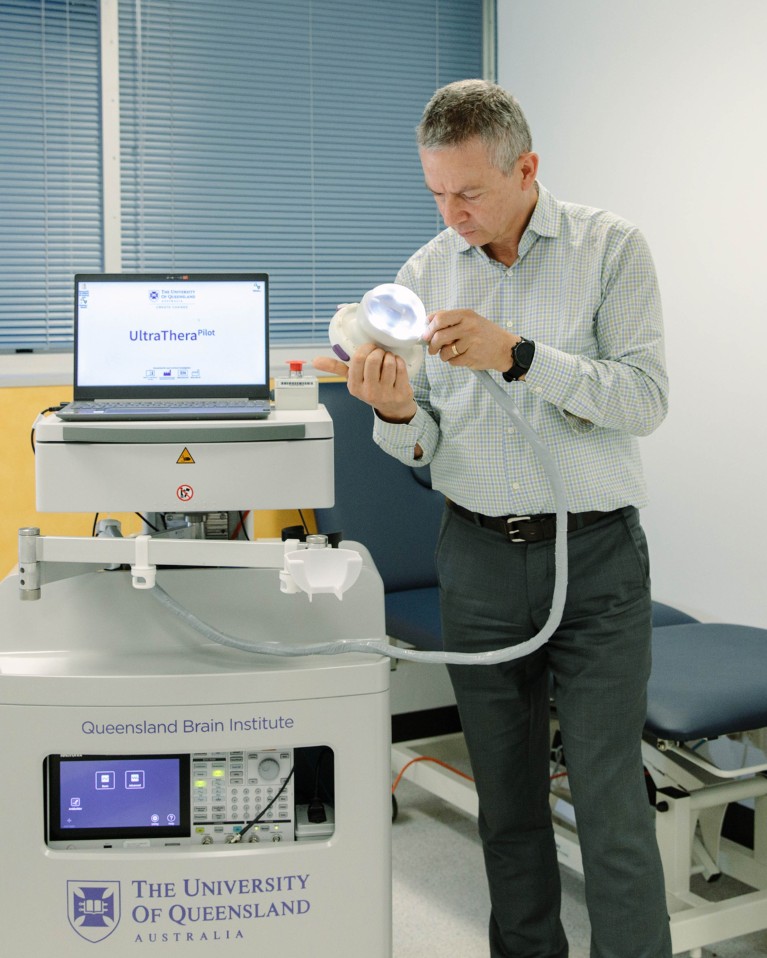

The team has completed a clinical trial to test the effects of low-intensity ultrasound in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Breaking barriers

With rapidly ageing populations globally, the number of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias is projected to dramatically increase. (Continued below video…)

Jürgen Götz, from UQ’s Queensland Brain Institute (QBI), says the recent FDA approval of amyloid-beta antibodies for treating early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in humans is encouraging but, as with other brain diseases, the challenge is to achieve high antibody levels in the brain in a localized and controlled manner. He believes that ultrasound may be the answer for antibodies and other drugs.

Götz began investigating the use of ultrasound as a treatment method when he joined QBI in 2012.

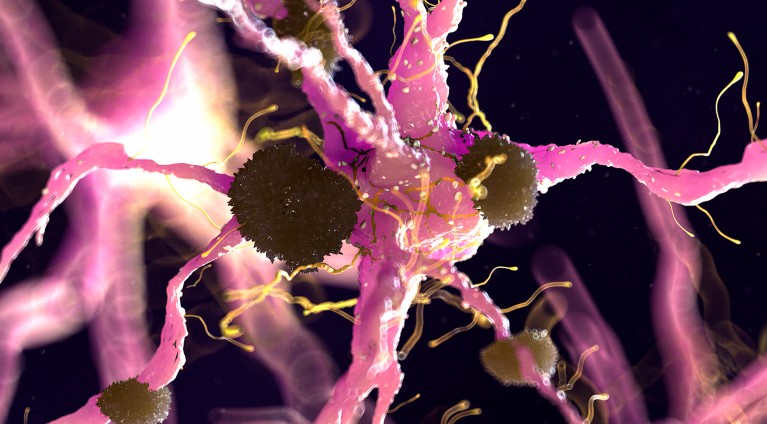

Using a strain of mice with an Alzheimer’s like condition, Götz and postdoctoral fellow, Gerhard Leinenga, combined low-intensity ultrasound with microbubbles injected into the bloodstream to transiently open the blood-brain barrier. This treatment reduced the brain levels of the characteristic amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s due to the activation of microglia, immune cells in the brain that clear the plaque. The mice that received this treatment showed improved memory and ability to learn.

They then used this treatment to deliver amyloid-beta antibodies into the brain of an Alzheimer’s mouse model and achieved both a reduction of amyloid plaques and also improved cognitive functions1. “We found that ultrasound when combined with microbubbles, can enhance the ability of antibodies to penetrate the blood-brain barrier more effectively and enhance the ability of immune cells in the brain to clear plaques,” says Leinenga. “It also allows for a more localized and controlled antibody delivery.”

Bursting the bubble

Then, in a major discovery for Alzheimer’s research, Leinenga and Götz demonstrated that low-intensity ultrasound alone — without the microbubbles — can deliver cognitive improvement in mice, potentially counteracting progressive amyloid-beta toxicity and increasing the brain’s cognitive resilience.

“Surprisingly, we found that cognitive function can be restored without removing the amyloid-beta,” explains Götz. They were in fact able to induce improvements in the memory of their mice just by applying ultrasound to the brain, he says.

This finding challenges the established notion that targeting and clearing amyloid plaques is necessary to improve cognition in Alzheimer’s disease.

While the mechanism is still unclear, it is possible that the stimulation caused by ultrasound soundwaves may enhance synaptic activity and improve brain function, speculates Leinenga.

“We believe that ultrasound, even without opening the blood-brain barrier, activates neurons and glia through mechanical stimulation, which could enhance connectivity and plasticity in the brain,” he says.

The researchers will now explore whether rethinking the link between amyloid-beta and cognition in these mouse models could have important implications for Alzheimer’s disease treatment strategies in people.

In the future, Götz foresees the possibility for a combination of therapeutic strategies aimed at both amyloid plaques and cognitive resilience.